America

Emigration

Einstein left Germany in 1932, apparently for a three-month vacation.

He knew deep down that he would never return. The rise of anti-Semitic

sentiments in that country made his life increasingly difficult. Hitler's

increasing popularity, which blamed the Jews for the stagnant economy,

only made the situation worse. Hitler eventually came to power in 1933 as

Reich Chancellor of Germany. A month later, Einstein learned that his apartment

in Berlin had been broken into and that he was on Hitler's list of prominent Jewish

figures to be killed. Later that year, Einstein made a last visit to Zurich and,

via Belgium and England, applied for permanent asylum in the US.

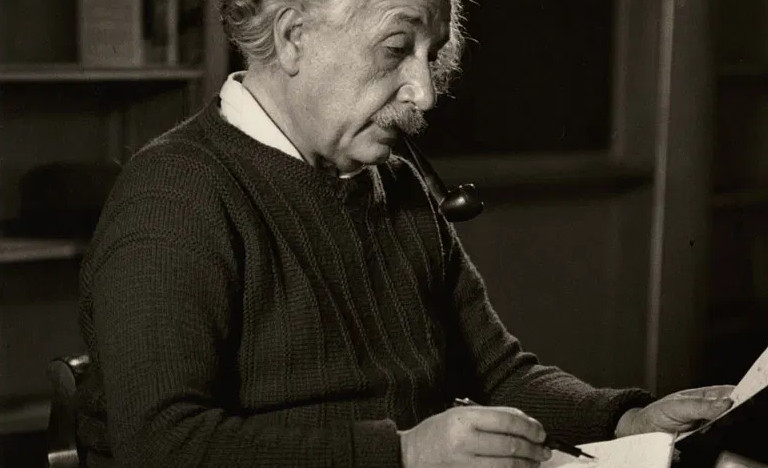

Einstein was approached to help set up a new research center in Princeton,

the Institute for Advanced Studies. After tough negotiations (Einstein demanded,

among other things, a vacancy for his assistant Walther Mayer, who was also a Jew

and therefore sought refuge), he not only had a new home, but also a new job.

Land of Freedom

The American doctrine of freedom of expression, free thought, and individualism was very similar to Einstein's own values. He lived on an immigration visa in Princeton for several years before passing the formal test necessary to obtain U.S. citizenship on June 22, 1940. He was sworn in as a full-fledged American on October 1 that year. However, not all Americans welcomed him with open arms. The right-wing Woman Patriot Corporation warned the Home Office that Einstein's radical theories and ideas were dangerous to the American way of life. Einstein simply laughed at this accusation.

The War

In 1933, Leó Szilárd, a young Hungarian physicist, devised a process that

generated energy according to Einstein's formula E=mc2, as well as

particles that would collide with other nuclei, thereby generating that energy as well.

Six years later, in 1939, Szilárd realized that the newly discovered uranium

could trigger a "nuclear chain reaction", enabling an unprecedentedly powerful bomb.

Szilárd contacted Einstein, with whom he had previously worked and convinced him

to use his influence to approach President Roosevelt directly.

Einstein warned the president that if Germany had uranium it could make an

"atomic bomb" and urged him to contact American nuclear scientists.

Historians agree that the letter that Einstein sent to Roosevelt was the main

impetus behind American efforts to develop a nuclear bomb, the Manhattan Project.

Nevertheless, as a German socialist, Einstein was denied access to the project,

he contributed indirectly to the bomb by developing a technique in Princeton

that separated the different isotopes of the radioactive uranium.

Although Einstein was hardly involved in the Manhattan project,

he contributed to the war in a different way. For example, he mathematically analyzed

the optimal pattern for placing sea mines in Japanese ports. The greatest contribution

was probably the self-written copy of the publication of his special theory of relativity

from 1905, which he offered for sale at an auction in Kansas City in 1944 for no less than

$6.5 million. He donated the money to the war fund.

The manuscript is now in the US Library of Congress.