The Young Genius

Einstein's Compass

When Einstein was very young, four or five years old, his father gave him a compass. He was fascinated by the way the needle reacted to an apparently invisible force, the Earth's magnetic field. This "distance attraction" of fields, especially the gravitational field, a force exerted by the mass of heavy objects such as stars and planets, would form a common thread in his later scientific research. It would lead Einstein to his general theory of relativity, probably his greatest achievement and still the best gravity theory. It also urged him to devote much of his later life to finding the unified field theory to unite all known forces of nature.

Reading

Albert's early interest in science was further stimulated in the late 1880s by a young man named Max Talmud. This devastated medical student ate with the Einstein family (a Jewish custom) once a week. Noticing Albert's burgeoning intellect and fascination with nature, Talmud took scientific books with him. The ten-year-old worked greedily through the famous works of the time. When he had finished all of Talmud's books, he switched to mathematics, geometry and then philosophy.

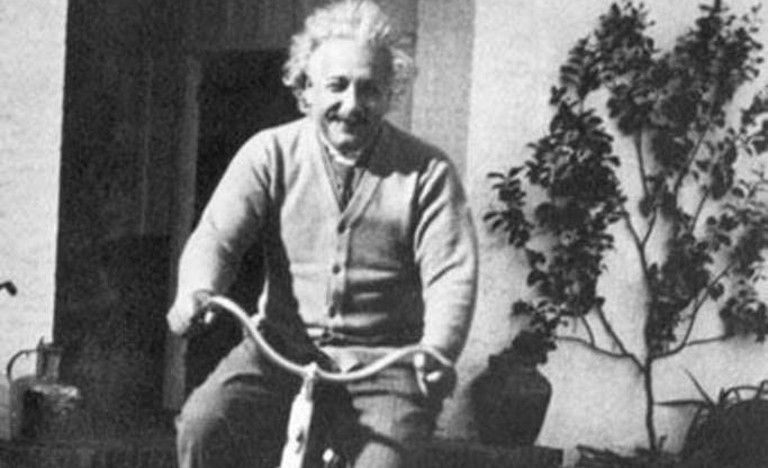

Cycling on a light beam

In 1895, sixteen-year-old Einstein was gripped by one of the most important thoughts of his entire life. He wondered what it would be like to cycle on a light beam. If light moved like any other object, the beam of light would appear to have stopped, relative to Einstein on his bicycle. Einstein would discover that the opposite was true. Ten years later, this simple idea had evolved into a theory that would revolutionize the way we think about light, fast-moving objects and the real nature of space and time.